(The City of Hampton and Fort Monroe will commemorate the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Africans in America August 23-25.)

By Lee Graves

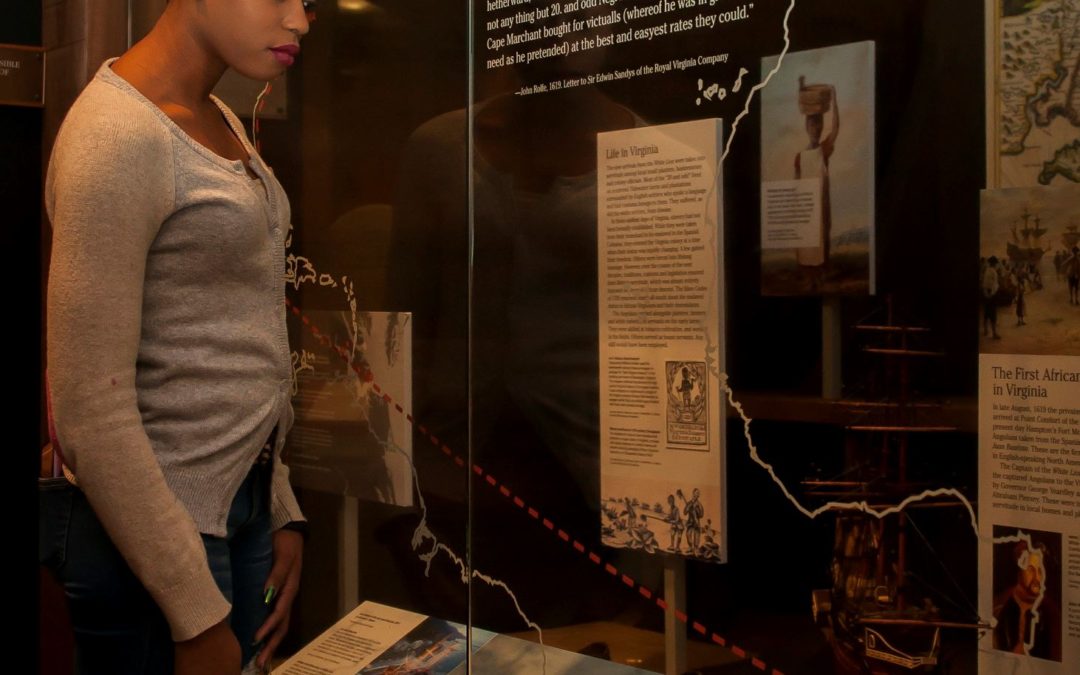

In late August 1619, the British privateer White Lion arrived at Point Comfort, near present-day Hampton. Its cargo included scores of Africans who had been captured that summer from a Spanish vessel, the San Juan Batista.

Thus began slavery in Virginia.

A month later, in September 1619, another British vessel, a bark called the Margaret, set sail from England for Virginia. The passenger list included more than a dozen indentured servants, men who would ply their trades for a set number of years and then be granted land and freedom. Among the cooks, carpenters, sawyers and coopers was a man named Thomas Perise. His purpose? “For hops,” the record reads.

These events four centuries ago might seem to have little in common. Yet slaves and indentured servants played an important role in growing hops and brewing beer in early Virginia, and their story adds a rich chapter to American history.

Beer had already made its debut. The English settlers who landed at Jamestown in 1607 carried ale, long considered a staple for its nutrition and as a safeguard against drinking contaminated water. That first crew, however, did not include any brewers, an error soon remedied in subsequent arrivals.

Brewing good English ale required hops, and despite the species being native to Virginia, the founding farmers gave a high priority to cultivating the crop—just as they found good use for slave labor. “There were in Virginia, in 1648, about fifteen thousand English, and of negroes that had been imported, three hundred,” according to one agricultural report. “The abundant crop of barley supplied malt, and there were public brew-houses, and most planters brewed a good and strong beer for themselves. Hops were found to thrive well.”

Indeed, hops were regarded as a staple commodity. The Virginia legislature passed a law in the session of 1657-58 providing premiums for several crops, including “hopps at twenty shillings per hundred.”

The reference to planters brewing “good and strong beer for themselves” begs clarification. It was generally the planters’ wives who made sure ale and cider were readily available, and often their role was supervisory. Slaves did the actual mashing and fermenting in the kitchen, we can assume, although few records exist because enslaved people were regarded as property being bought and sold. An ad in the June 6, 1745, Virginia Gazette, though, includes brewing among desired skills: “To be sold to the highest bidder: A Valuable young Negro woman, very well qualified in all Sorts of Housework, as Washing, Ironing, Sewing, Brewing, Baking.”

Just as slaves did the hands-on brewing, they bent their backs among the hop bines on Virginia’s plantations. Landon Carter, son of Robert “King” Carter and one of Virginia’s gentry in Revolutionary times, wrote a 16-page treatise on hops cultivation in the mid-1700s. His essay describes soil preparation, cultivation, picking, drying and bagging. Was he actually in the fields doing the hoeing and harvesting? Unlikely, as his estate had some 500 slaves.

Because hops were a prevalent crop and slaves were the backbone of field labor, it’s easy to assume that enslaved workers learned not only the value of hops but the art of growing them as well. No wonder they began turning their knowledge and skill to their own advantage, in their own gardens.

Indeed, numerous records show plantation owners and brewers purchasing hops from African Americans. A ledger for the brewery at the College of William & Mary shows “Paid Nottoway Negroes for Hops” in a December 1775 entry. George Washington’s accounts show a payment in 1798 for six pounds of hops to one Boatswain, a “ditcher” at Mount Vernon’s Mansion House farm.

The records of Thomas Jefferson, and his wife, Martha, provide more details. An avid and highly regarded home brewer, Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson bought hops from Monticello’s slaves. She bought hops from neighbors’ slaves. She bought hops from slaves in Williamsburg. “Hops was among the most frequently purchased product from the slave community by Martha,” wrote author Peter Hatch, former director of gardens and grounds at Monticello. In one journal entry, Martha notes trading seven pounds of hops for “an old shirt.” While she doesn’t name the seller, it takes only a small leap of curiosity to ask, “Who would want an old shirt?”

The most eye-opening transaction occurred in 1818. Thomas Jefferson paid $20 to Bagwell Granger, a notable figure in Monticello’s slave community, for sixty pounds of hops. Sixty pounds! Wet or dry, that’s a lot of hops, and one wonders if it might have included some wild hops in the bargain. And $20! In today’s economy, that would equal about $800.

It is at Monticello that we also find perhaps the most notable intersection of beer and slavery in Virginia. Though known widely as a wine lover, Jefferson was also a beer geek. He grew hops. He built a malt house. He designed a brew house, though no record of its construction exists. He sought books about brewing. Because barley was expensive to import and did not grow abundantly in Virginia (despite the 1648 report), he experimented with brewing beer with corn and wheat.

After his two terms in the White House, circumstances afforded Jefferson the opportunity to up the ante on brewing at Monticello. During the War of 1812, a former professional London brewer named Captain Joseph Miller returned from England to his native America to claim family estates. A series of misfortunes—and suspicion about his English ties during wartime—left him stranded in Albemarle County. Jefferson befriended him and asked him to share his brewing expertise with one of his slaves.

That man was Peter Hemings, son of Elizabeth Hemings, brother of Sally Hemings and half-brother to Martha Jefferson herself. Peter Hemings was already a skilled tailor and chef. Miller and Hemings began brewing at Monticello in September 1813, and Peter proved a quick study. Jefferson described him as possessing “great intelligence and diligence both of which are necessary.”

Brewing was seasonal, and the quantities dwarfed Martha’s 15-gallon batches. “We brew 100 [gallons] in the fall & 300 [gallons] in the spring,” Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1821 to James Barbour, a former governor of Virginia and a U.S. senator at the time. “Peter’s brewing of the last season I am in hopes will prove excellent. At least the only cask of it we have tried proved so.”

Jefferson invited others, such as James Madison, to send slaves to learn from Hemings. “Our malter and brewer is uncommonly intelligent and capable of giving instruction if your pupil is as ready at comprehending it.”

A sadder tale at Monticello serves as a reminder of slavery’s harshness. Nance Hemings, the third daughter of Elizabeth Hemings and kin to Peter, worked there as a weaver, cook and brewer, according to the estate’s records. She and her two children, Billy and Critta, were given to Jefferson’s sister as a present in 1785. However, 10 years later Jefferson needed a weaver, so he bought Nance Hemings back for sixty pounds; he did not, however, buy either of her children. Thomas Mann Randolph, Jefferson’s son-in-law, did purchase Critta. When Jefferson’s estate was auctioned in 1827 to repay debts, Nance Hemings was listed as “Worth nothing” and became the property of Randolph.

At the same auction in 1827, Peter Hemings was purchased by Daniel Farley, a free black man in Charlottesville who allegedly was his nephew. Farley also was a hops grower—he sold an unknown quantity to Thomas Jefferson in 1812 for $1.33.

Thanks to the labor of slaves, Virginia was the leading hops producer in the South in the decades leading to the Civil War. The 1862 report of the Department of Agriculture shows the Old Dominion producing 10,015 pounds of hops in 1860, the most by far among the “disloyal” states in the report.

That war led to emancipation, and nearly a century later federal legislation codified civil rights. Yet our nation still struggles with racial issues. Acknowledging the roles of enslaved people in our history is a step toward deeper understanding, and what better way to do that than over a beer.

Lee Graves is an award-winning beer writer and author of numerous books including Virginia Beer: A Guide from Colonial Days to Craft’s Golden Age.